Mel Gibson for Dummies: Hollywood Hunk Becomes Infamous Film Icon

What do you get by taking a kid from New York, depositing the kid down under in Australia, and letting loose the kid in the streets of Hollywood? You get Mel Gibson—a person who managed to convince the world he could win an Oscar for bellowing the word “FREEDOM!” in a kilt. But isn’t that the madness of Hollywood magic?

Early Years: From Peekskill to Sydney

Born in Peekskill, New York, on January 3, 1956, Mel Gibson began the first of the big adventures in life when he was 12 years old—involuntarily, of course, not of his own accord, but when the family determined Sydney, Australia, promised more than small-town America. Try to picture this: A preteen American youth abruptly deposited in the land of Vegemite and cricket, with most likely a mind-set where everyone spoke upside down. Nobody could have believed this oceanic swap would spawn one of the most riotously over-the-top action heroes on film.

Youthful Mel sat in front of the National Institute of Dramatic Art with no doubt thinking about the point of performing Shakespeare with an Australian accent in paying off the mortgage. The response came speeding down a post-apocalyptic road in the form of leather-clad avenging angel Max Rockatansky.

The Mad Max Era: The Action Icon Emerges

When in 1979 the crowd beheld the otherworldly and wondrous spectacle of a previously unknown actor turning smashed automobiles into stunning works of art, Gibson did not precisely drive but was the car and traversed the flat wastelands of Australia with the frenzy of a cabled dingo with suicidal instinct. Not merely did the Mad Max sequence of 1979-1985 turn Gibson into a star but the patron saint of car anarchism and post-nuclear cool.

Yet the trouble with Hollywood success is that one is not sufficient. Why one quintessential character when you can have another?

Inner City Killers: The Art of Managed Violence

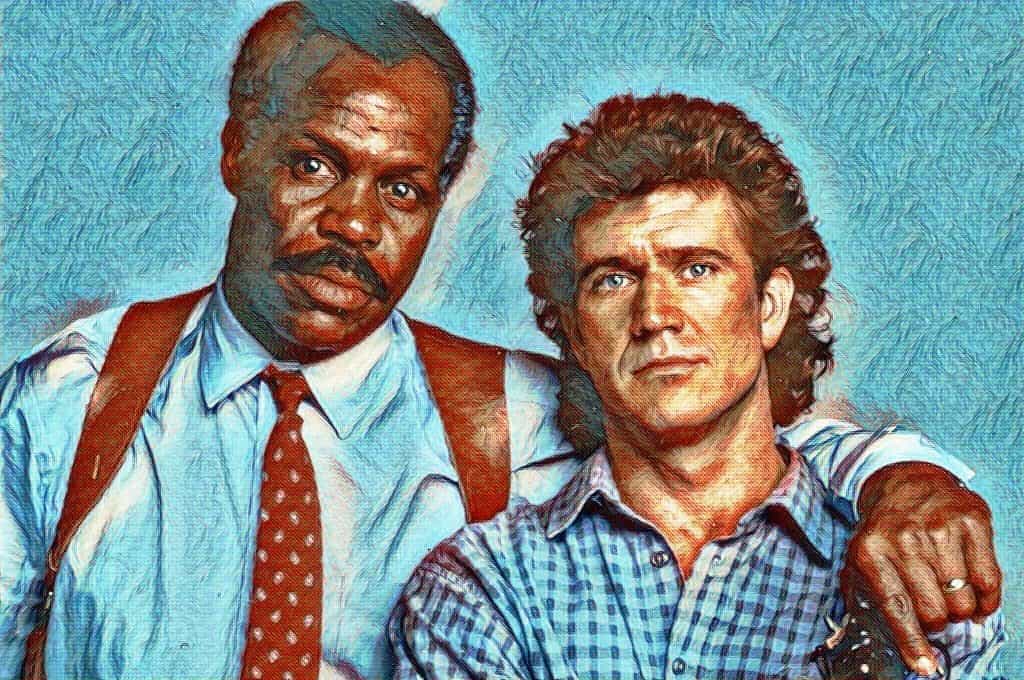

We of the tail-end of the 1980s were privy to such fare as the Lethal Weapon movies where Gibson honed the character of Martin Riggs—a cop so crazy, technically being insane was not so much an issue of building character as of job requirements. Four flicks of Danny Glover telling him he was “too old for this,” as Gibson honed the craft of the line to and beyond method acting being happily obtuse.

What’s remarkable about this collaboration is the form in which it took: Glover the voice of reason and Gibson the personification of sheer, unadulterated madness. You’re sitting there watching some philosophical debate on sanity and beautiful madness with plenty of pyrotechnics.

Braveheart: The Kilt That Won Hollywood

Then came 1995, and Gibson relaxed and thought to himself: “You know what this career could use? A little more kilts and thirteenth-century fight scenes.” And so came Braveheart–a film in which Gibson starred, but of course also produced and directed, because apparently monopolizing the whole process of making adult men sob over the freedom of the Scots was where he perfected the art of getting hired for things.

The film swept the Oscars and captured the Golden Globe and Academy Award for Best Director for Gibson and the most prized Best Picture Oscar. Not bad for a war-painted warrior who wields a claymore and grimly slaughters Scottish history.

The Scandal Years: Religion, Scandal, and Box Office Hits

Gibson’s directorial track took a bizarre turn with The Passion of the Christ (2004), proving he could also ignite scandal and rings on the box office bell. He followed the biblical epic with returning the people back to ancient Mesoamerica in Apocalypto (2006), because nothing says “career diversification” like making people have to read subtitles and run around jungles and避 obsidian-sharpened darts.

But here’s where things get interesting and complicated with Gibson’s case: personal scandals spawned a Hollywood exile of longer duration than some ancient civilizations, causing fans to wonder if the world would ever see of him again working behind the camera.

The Redemption: Hacksaw Ridge and Redemption

Back from the dead after all those years, Gibson returned to the director’s chair on Hacksaw Ridge (2016), and with two Oscars in the bag, he reminded us the greatest comebacks are conscientious objection and gut-level World War II combat scenes. He seemed to be thinking, essentially, “You want to see me on A-game? Watch this.” The Gibson Heritage: Passion, Controversy, and Movie Magic What could Mel Gibson’s roller-coaster life perhaps have in store for us? Maybe this: in Tinseltown, scandal and genius frequently tango as old lovers who can’t possible break up with each other. Along the highways of Australia, from the battlefields of Scotland to mythic legend, Gibson has spent decades demonstrating the following: with sufficient passions, intentional bellows, and genius-level expertise in transmogrifying any era into raw cinematic alchemy, you can survive pretty much anything—yourself first and foremost. Still isn’t it remarkable the way the life of one American city kid born in the Big Apple to OC transplant to Hollywood icon so perfectly distills the madness of the entertainment business? I mean, in a fantasy business, who better to flourish than the one who so totally believes in the illusion you can’t keep straight where the actor stops and the man begins?

How Mel Gibson’s Kin Discovered and Controlled Relocation Worldwide

A Saint-Sized Naming Convention

Just imagine: A baby in Peekskill, N.Y., who’s going to turn into the most divisive man in Hollywood. But hold on—you’re not finished yet. This isn’t any normal baby. This is Mel Columcille Gerard Gibson, who’s going to become the eleventh of twelve kids. Because when you’re Irish Catholic, you’re not going to have children; you’re going to have a mini-city into the world.

Then there’s the middle name—Columcille. Sounds like the kind of thing you’d insist on mispronouncing obstinately over expensive Irish food, doesn’t it? “Waiter, I’ll have the shepherd’s pie and a generous portion of Columcille, please.” But poor little Mel had so properly been named after St. Mel of Ardagh, and the middle name is in honor of one of Ireland’s patron saints, St. Columcille. Because when you’re this actually Irish, one divine patron isn’t going to cut it. You want backup saints—religious insurance, if you please.

The Cultural DNA Scramble

When you speak of Irish authenticity, this pedigree reads like a geography textbook looking for an identity. Dad, Hutton Gibson, was a novelist (of course, dramatic flair is in the family genes), and mother, Anne Patricia Reilly, fresh from the Emerald Isles with the entire inflection still present. But where genetics strangely enter into the equation in the case—Mel’s grandfather on the father’s side, Eva Mylott, who by the way was born in Australia but came from Irish parents who must have serenaded their evenings away warbling about homesickness in operatic style.

And the Irish-Australians with future Irish-Aussies on the hip and someone doing scales in the background. That’s the cultural GPS with perennial indecision, re-calculating left and right between Dublin and Sydney and “somewhere with tolerable tea”

The intrigue thickens even more with the arrival of his grandfather as the figure of a millionaire American Southern tobacco tycoon on stage left. Because nothing encapsulates “unified family story” like the juxtaposition of Irish Catholic conscience and Southern American tobacco benevolence with the opera singing Aussies who most certainly fought over correct diction at Sunday roasts.

The Great Pacific Escape

But wait—there’s more family soap opera to follow. In 1968, when teenage Mel was twelve and probably honing his brooding look, dad Hutton was a courtroom winner. He received $145,000 in a suit against the New York Central Railroad for a work-related injury (that’s more than a million dollars today for those keeping score on their own form of escape).

Did he buy real estate? A sensible sedan? Not on your life. Rather, he came up with the most complex family move of the modern world and packed all eleven Gibson spawn like a vagrant circus with the Ringling Brothers and moved the whole genetic circus to West Pymble, Sydney, Australia. Why Australia? Because it had twin aims with the martial flexibility: showing respects to grandma Eva’s homeland and—to use the master chess strategy—getting the oldest son to sidestep the Vietnam War draft altogether. What better example of ahead thinking than moving the whole line of descendants halfway across the Pacific in order to sidestep the draft? That’s chess on the global board, except the most glaring difference is the pieces are kids and the chessboard is transcontinental.

The Learning Finale

Once firmly established Down Under, young Mel ended up in St Leo’s Catholic College, Wahroonga, the culmination of the educational work of the Congregation of Christian Brothers. Appears after going half way across the world, evading the draft, and putting together the most cosmopolitan family group the world has seen, the Gibsons were not yet done filling out their quota of responsibility to Irish Catholic traditions of education. And there you have it–the build up of a Hollywood legend, with global tension, calculated moves, and one heck of a collection of Irish Catholic inside jokes in one film.

From Mad Max to Masterpiece: Mel Blunders Into Directorial Brilliance

The Twist That Nobody Expected

Just picture it: You’re one of those hard-man Aussies who struts into Hollywood, loaded with leather-assaultpants and a muscle car, and by morning everyone’s yelling the next Steve McQueen about you. Most actors would surf the wave into the bank, possibly sign on for a coupla more sequels, and surf the money in retirement on the returns. But Mel Gibson? He literally looked at his hard-man image and said, “This is cute, but picture me tears over Scottish independence instead?”

It’s to see Superman save he’d prefer to spend his time back there providing direction for Clark Kent. Gibson’s evolution from leather-clad road warrior to Oscar-winning director is more like one individual abusing the wrong script of Hollywood—and going on to achieve enormous success.

The “How Hard Could It Be?” Stage

First experience in director’s chair in 1993 with The Man Without a Face. He can even see the soundstage in his mind and imagine himself there with perhaps gestures and cups of coffee overlaid on the acting and directing–“I’ve sat back and watched people yell ‘action’ for years—how hard can this be?”

More complicated than you can imagine. But Gibson tackled film-making the way he tackled not blowing the heck up in Lethal Weapon: with unforeseen grace and with a strange gift for making the unmakeable look effortless. The film fared well, proving our tough-guy actor could handle the drama without blowing the heck up and still look cool—an epiphany which no doubt infuriated some of the moguls back east.

The History Lesson That Turned Everything Around

Along came 1995 and Braveheart, the movie that somehow managed to persuade millions of people that medieval Scottish fighters marched into battle sporting face paint in shades of blue as if to a match of their toughest football encounter ever. Historically accurate? Realistic as a medieval McDonald’s. Cinematically inspiring? Iconic to the nth degree.

Gibson did not simply direct this saga; he acted in this movie, produced this movie, and probably hand-sharpened each and every one of the swords in the process. The Academy Awards broadcast for the year was equivalent to watching Gibson receive Awards in some sort of over-the-top game show. Five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. The director who had already snubbed James Bond had gone and demonstrated to the world the best way to take over Hollywood is by directing an imaginary Scottish army and yelling about freedom.

Spiritual Enlightenment That Shocked Everybody

Just when one thought one knew Gibson, 2004 had other plans. The Passion of the Christ came to theaters in a flash of spirituality, grossing over $600 million on the worldwide box office and proving to the world the actor who had spent decades portraying a detective with a death wish could deliver one of the most spiritually fueled film experiences of modern history.

What Gibson used to do so assuredly in the direction of pyrotechnics has graduated into leaving middle-aged men questioning the heck if there even were people in a film. Reviewers could not decide if they were to pan the film or recommend sessions of therapy. Film-making as religious experience was the aftermath of a director who had already made headlines for innovative methods of getting rid of undesirable people.

The “Let’s Make This Really Interesting” Masterpiece

Yet Gibson’s most irresponsible direction came with Apocalypto in 2006. Try to imagine the pitch conference: “I want to do a running picture in pre-Columbian America with no known stars, subtitles throughout, and maximum ancient Mayan civilization so the archaeology people will bench their tears of joy.” Any sane studio head would have had him escorted from the premises in handcuffs. He succeeded despite, creating a gut-response masterpiece that demonstrated dialogue isn’t necessary when you know the strength of visual storytelling. Critics loved the tech know-how and viewers discovered you could be completely entranced by a movie in which not a single word could you understand. It was as if watching a master play the game of moviemaking at the expert level—and winning.

The Transformation Finished What’s remarkable about Gibson’s film life is

Not the quality of the films but the titanic, large-scale thinking with each and every one of the films. He tackles titanic, high-concept premises head-on with the same fervor he initially employed for car crashes and shootouts. With one difference? He’s the one conceptualizing the destruction this time and not merely surviving the wreckage. From action hero to director, Gibson recast himself as something that Hollywood isn’t usually prone to producing: a director who isn’t afraid to tackle sensitive subject matter, ancient civilizations, and metaphysical subject matter with an equal fervor. It’s so much of a career realignment so unanticipated and successful you can’t help but wonder about what other action heroes are hiding under directorial excellence. Although, naturally, most of those probably are hiding more action movies.

The Mel Gibson Years: From Drama Queen in Tutus to Hollywood’s Most Mysterious Anti-Hero

Fairy Queen Origins No One Saw Coming

Look at this amazing picture: it’s 1975, and in a Sydney drama school, would-be action hero Mel Gibson turns on pointe in a tutu as Titania, the fairy queen of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Yes, the same one who in subsequent movies snarled “I am Mad Max” once danced on pointe as the fairy queen. If this doesn’t make you question everything you ever thought about the testosterone-fueled path to Hollywood stardom, nothing will!

This delicious irony isn’t even better yet. Gibson and future Best Actress contender Judy Davis were star-crossed lovers back in the National Institute of Dramatic Art, walking the boards in Romeo and Juliet. We can only imagine the universe’s sense of humor in watching Gibson practice romantic sonnets unaware of the bomb-ridden future ahead of him and short on iambic pentameter.

The $9,000 Road Warrior Package

Once he graduated in 1977, Gibson dived headfirst into Mad Max—and by “dove headfirst,” I mean he received the grand total of $9,000 to become Australia’s most recognizable post-apocalyptic road warrior. To put it in perspective, that’s roughly the amount some people would buy a nice used car for in modern society. While Gibson went about launching a whole film genre, he launched said genre on the budget of a Honda Civic.

But there’s the sweet irony: the road warrior had not been domesticated by success. Gibson moved in on a $30-a-week Adelaide flat with one-day bride-to-be Robyn Moore.Thirty! Less than most of us pay for a breakfast coffee. The poetic justice is breathtaking—the man whose future paycheque would be comprised of figures in the range of $25 million used to share rent with less than the cost of a high-end meal.

The Chameleon Years: From Village Idiot to Naval Officer

Gibson’s starting career is a lesson in “fake it till you make it.” He grew from a retarded teenager in Tim to a naval lieutenant on The Sullivans, a sign that range isn’t something you create. The fellow accumulated roles as a completionist—had to do ’em all, if one is for a lost prison serial called Punishment that no one ever got a chance to see.

This ragtag strategy wasn’t just bold; it had sounded extremely shrewd. Gibson was building an acting resume that would serve him well when Hollywood came knocking.

American Invasion: Feeding the Road to Success

Hollywood came knocking in the form of The River, where he and Sissy Spacek played one of the Tennessee farm strugglers. Because, seemingly, the American film formula for success is to pretend you understand farm economics. But still Gibson hadn’t revved the cylinders.

And then came 1987, and Lethal Weapon, the film that made Gibson more than upstart newcomer, but bona fide movie star, Hollywood’s dealer of choice in controlled chaos. Martin Riggs was a seismic event more than a character. Gibson had hit a sweet spot—that nice juncture of “I’m too old for this” and “here I go leaping off this roof anyway.”

The Golden Nineties: Scottish Voices and Colonial Empire-Building

The 1990s were Gibson’s imperial decade, as the actor shuttled between commercial hits and personal obsessions like a Hollywood DJ spins personal favorites and left-field deep cuts. He voiced John Smith in Pocahontas (what better way to describe colonial expansion than an Australian drawl?), parodied a supposed Scottish brogue in Braveheart, and collected a then-record $25 million for The Patriot.

This decade put Gibson in his most powerful forms: director, star, and cultural phenomenon in one un-deniable package.

The Fall: When the Music Stopped

This is where our story takes a turn even the most crazed scriptwriters in Hollywood could not have conceived of. Sometimes the most fascinating thing about any scandal is not the rise—but the fall, as the power of gravity reasserted itself. Gibson’s latter years was a lesson about the transitory nature of reputation, showing the image in Hollywood to be more delicate than a soap bubble in a tempest. Scandalous remarks and on-streets tantrums made Gibson from everyone’s darling a studio pariah quicker than you can say the words “career suicide.”

The Villain Years: Hollywood’s Most Candid Career Detour

But Gibson continues to resurface in front of us as the only friend who continues to attend parties even after he’s “banned” for the past three. He’s created a second profession as the villain-for-hire of Hollywood with movies such as Machete Kills and The Expendables 3. Is this the pinnacle of Tinseltown career makeovers, or the most complex method acting exercise to ever go into production? Either way, Gibson has managed to take in-life on-screen scandal and turn it into in-life on-screen drama. That alone? That’s lemons and lemons and lemons into box office lemonade!

The Mel Gibson DirectingSaga: An Exploration of the Most Fascinating Enigma in Hollywood

The Reluctant Director

Just imagine: 1989 comes along and film producers largely are down on bended knee in supplication to Mel Gibson and see if he can and would want to direct. He says? A curt “thanks, but no thanks” because nothing says the next Academy Award winner like flatly turning down the one thing you’ll become a household name for, right? It’s like turning down the lottery ticket because you don’t want to deal with the ramifications of all the money.

Skip ahead to 1993 and our reluctant protagonist cracks under the strain and becomes the director of one film in The Man Without a Face. Two years down the line, he’s hoisting up the Oscar for Braveheart and no doubt thinking he wished he had done this sooner and become a director of men who love to tell other people where to stand and where to feel.

The Project That Got Away (And Other Hollywood Flops)

Gibson also grandly plotted to re-create Fahrenheit 451—yes, that bright little story of books on the bonfire. But in 1999, dates clashed down like an aggrieved studio mogul, and the film went into development hell. Meanwhile, he would direct Robert Downey Jr. in a stage production of Hamlet. What could possibly go wrong with the combination? Well, as one can see, lots of things. The backslide into drug-use of Mr. Downey derailed the project sooner than one could utter the phrase “To be or not to be. probably not to be.”

The Passion Play

In 2002, Gibson laid down the acting mantle and took up the directing one. What’s next? A low-radar constructed film called The Passion in Latin and in the Aramaic with no subtitles, because seemingly Gibson had faith in the universal language of suffering. The man wanted to “transcend language barriers for filmic storytelling”—or in Hollywood speak, “let’s see if people are going to watch a motion picture where they have no idea of what the heck is going on.”

Plot twist: they would absolutely do. The Passion of the Christ capitalized on any R-rated movie of all time, earning more than $370 million in US box office. No one would’ve thought unintelligible language would be a box office hit.

The Ancient World Tour

Gibson appeared to have a weakness for historical epics in which actors used dead languages. After The Passion, he treated us to Apocalypto in 2006—a film in which one could lose the sound of the actors’ voices but never the spectacle. Gibson had discovered that subtitles are his trump card, and film audiences reluctant experts in ancient history.

The Viking That Never Was

What’s Gibson’s next blockbuster? A Viking epic with Leonardo DiCaprio, of course with lines in languages of the times because who wants to mess with tradition? But Leo had already had one lifetime of inaudible lines and had no share of those either. The film, in a working title of Berserker, still lingers in the mythical Hollywood realm where fantasies are left to wait for all of forever.

The Maccabees Mish

Gibson brought in Joe Eszterhas in 2011 to write a film about the Maccabees. What ensued was a Hollywood soap opera more gripping than most real movies. Eszterhas alleged Gibson of usurping their project and put up the incensed open letter slinging more mud than a broken washer could ever contain. Gibson’s reaction? The script had initially been poor to begin with. Eszterhas then alleged Gibson of covertly recording the actor’s supposed rants. At this point, the film about the Maccabees had spawned more scandal than most movies garner in profits.

The Resurrection Business

In 2016, Gibson announced plans for The Passion of the Christ: Resurrection, once more with Braveheart screenwriter Randall Wallace. Because what are you actually doing with a sequel to a polarizing religious epic besides going for the whole shebang? The film has lingered “three years off” for maybe seven years now, and in Hollywood-time, this makes it more or less greenlit and ready to go.

War Stories and Remakes

One not to stick around in the limelight of scandal (or laurels), Gibson has promised to direct Destroyer, yet another WWII film/flyboy action of the repelling of 22 kamikazes by the USS Laffey. He’s equally promised to remake The Wild Bunch and direct Lethal Weapon 5, retirement apparently not in Gibson’s lexicon.

The Gibson Method

What’s motivating Gibson as a director? According to accounts from people who’ve worked with the director, he’d prefer to release tension on-the-set by having actors do dramatic scenes with red clown noses on. Helena Bonham Carter nicely described his sense of humor as “lavatorial and not very sophisticated.” Easter eggs are also a thing Gibson enjoys, having included one frame of himself smoking in one of the Apocalypto trailers—because nothing shouts “ancient Mayan culture” like a guy with a cigarette.

The Ruling

Love ’em or loathe ’em, Gibson has forged a personal niche in Hollywood: the director who keeps you on the mental treadmill. Whether he has you deciphering subtitles in Latin or has you running for cover to fend off kamikaze aircraft, one thing’s for sure—you’re on the edge of your seat with a Mel Gibson film. In a world where safety first is the mantra of the movies, maybe this is the very formula required: a director who never looks back on putting audiences in the position of thinking, flinching, and often reaching for their glasses.

Mel Gibson Directing: A History of Holy Warriors, Viking Aspirations, and Red Clown Noses

The reluctant genius who wrote “Thanks, But No Thanks”

Can you imagine? 1989, and film moguls are nearly genuflecting to Robert Downey Jr., begging the actor to try to convince his pal Mel Gibson to give directing a shot. Gibson’s response? A polite but firm “Thanks, but no thanks.” Fast-forward a few years, and look! Everybody’s calling him “Oscar winner Mel Gibson.”

Irony of fate, isn’t it? The greatest directors are often those who need to be dragged kicking and screaming into the presence of the camera.� You’ve got one of those kinds of people who’ll turn down a winning lottery ticket but are still complaining about the day job

The Accidental Auteur Finds His Calling

Gibson eventually relented in 1993 with The Man Without a Face—since clearly, when Hollywood knocks and knocks and keeps on knocking, even the thickest door creaks open eventually. Braveheart, however, turned the unwilling viewer into film dynamo and earned the reluctant director the coveted Academy Award for Best Director.

Pretty good for the person who initially rejected the position, though? It’s as if the person unwittingly discovers their profession by accident in the act of getting out of it. The cosmos has a funny sense of our fates occasionally.

When Drawings Go Up in Smoke

That’s where the story of Gibson becomes richly complicated: he had bigger plans to re-make Fahrenheit 451, but in 1999, schedule conflicts popped that balloon sky-high sooner than Bradbury’s repressed books. And who can forget the cult example of Gibson directing Robert Downey Jr. in Hamlet?

Well, fate had other plans in January of 2001, and Downey’s personal demons had other ideas about that shoot. Sometimes the most poetic of projects are ruined by the most unpoetic facts.

The Passion Project That Would Not Make Sense

In 2002, Gibson announced he would quit acting to direct full-time. Grand entrance? Some humble little film titled The Passion—in the old locals’ and dead Romans’ tongue, no subtitles. Because who needs to hear lines when you’ve “pure filmic storytelling,” eh?

Well, subtitle sanity prevailed, and The Passion of the Christ went on to actually finish as the then-highest-grossing R-rated film, at more than $370 million. Not bad for a guy who didn’t even want to direct anything. It is like watching someone stumble into making fire by not wanting to get burned.

The Viking Dream That Set Sail

And who would forget Gibson’s Holy Grail: a Viking epic featuring Leonardo DiCaprio? Try picturing this—actual life era slang, fatal Nordic battles, and Leo most likely sporting yet another epic beard. Sounds epic, huh?

Well, DiCaprio left it faster than a Viking running away from a well-guarded monastery. But did Gibson concede? Of course not! In 2012, he announced Berserker kept going in production. Because nothing shouts dedication more loudly than the fervor of hanging on to a film once your A-list lead has sailed away to greener fields.

The Maccabees Mess: When Collaboration Goes Nuclear

Gibson hired Joe Eszterhas to write a Maccabees film in 2011. What could go wrong? Everything, as it would turn out. In April of 2012, Eszterhas was writing indignant letters accusing Gibson of ruining their screenplay, with accounts of so-called secretly recorded “hateful rants.”

Gibson’s response? Essentially, “Your script stinks, and I’m making this movie anyway.” He made comparisons between Maccabees saga and American Old West genres, because apparently, ancient Jewish rebellion and cowboys have more in common with each other than you’d realize. Sometimes creative partnerships end in a bang bigger than the story they are attempting to tell.

The Resurrection of Ambitious Storytelling

In 2016, Gibson announced The Passion of the Christ: Resurrection—why not? If once possible, why not reissue? He estimated the film would come in three years because “it’s a big subject.” Well, Mel, stories of resurrection don’t happen on their own, do they? The film has seemingly gone into production in the month of January 2023, with film critic Matt Zoller Seitz proclaiming Gibson “the preeminent religious filmmaker in the United States.” Not bad for the director who began with tentative directing cues by Robert Downey Jr. Sometimes the biggest things have the most unusual of beginnings.

War Stories and Hollywood Mad Libs

Gibson’s World War movie obsession transferred to Destroyer, another WWII Pacific Theater story of the USS Laffey crew fighting off 22 kamikazes. Clearly, neither World War movie about the battle of Okinawa was sufficient in feeding his war drama appetite.

And then there’s the remake of the Wild Bunch with Michael Fassbender, Jamie Foxx, and Peter Dinklage potentially starring. Jerry Bruckheimer producing, Warner Bros. backing—it’s like a game of mad libs Hollywood, except with actual money at stake. It’s usually the most unlikely pairings that make for the most compelling possibilities. The Person Behind the Red Clown Nose What motivates Gibson as a director? From the inspirations he has—George Miller, Peter Weir, and Richard Donner—it’s the refinement of the craft. But here’s the tasty paradox: Gibson also diffuses dramatic tension on the set by having actors perform intense scenes in front of red clown noses. Helena Bonham Carter has referred to his character in the following way: “He has a very simple sense of humour. A little lavatorial and not very high-brow.” Try one on for size: Gibson has even featured one of him taking a fag break in the Apocalypto teaser trailer. Why not have a smoke break in your ancient epic about the Mayans? The Beautifully Contradictory Journey Red-nose-clown comedian, Oscar-winning and reluctant director, Mel Gibson’s filmography exists in defiance of all the Hollywood how-to books. He has scripted ancient world epics, religious blockbusters, and war pictures—all without seeming to master any of the traditional Gibson arts of directing pictures. The one who, previously, clung to not directing is America’s finest religion-based film director of today. Not bad for one who detonates dramatic tension with bathroom jokes and ninja-like cameos for puffs. At other times the most improbable routes are the most jaw-dropping destinations, don’t one think?

Mel Gibson’s Love Ride: A Chronology of Passion, Heartbreak, and Courtroom Battles

Ever feel like your love life has been picked apart by tabloid writers with the precision of forensic pathologists? Try Mel Gibson—though he’ll likely complain about “freedom” and slowly limp off in slow motion in the manner of a dramatic escape sequence.

Mad Max: A Love Story Begins (1977-2011) and the Dental Assistant

Imagine this scenario: It’s 1977 and John Travolta is teaching the masses the way of disco, and on one of the streets in Adelaide, Australia, budding actor Mel Gibson encounters Robyn Denise Moore, a dental nurse. She’s perhaps thinking, “Nice teeth—clearly he flosses,” and he’s thinking, “This woman can deal with my special brand of crazy.” Three years go by—boom!—Catholic wedding bells are ringing in Forestville, uniting for life to bear more young’uns than an Animal Planet special.

What ensues is a suburban fairytale penned by someone who apparently never heard of the existence of birth control: seven kids in the course of almost two decades. Hannah enters the picture in 1980, and in 1982, the twins Edward and Christian are born (because why settle for one restless night when you can have two?), then William, Louis, Milo, and finally Thomas in 1999. Gibson’s home at this juncture had to look like nothing so much as a daycare center conceived by someone with extremely serious commitment issues.

This for 26 years was Hollywood’s strongest marriage—a unicorn in a world where engagements barely lasted longer than the expiration date on milk in the fridge. Robyn steadied Gibson as he tore through Hollywood one heart-stopping action sequence after another. Robyn observed Gibson transform from anonymous Aussie actor to directing Oscar winner, probably wondering if she had wedded Clark Kent or maybe unwittingly slept with Kent’s deranged alternate personality.

And then July 29, 2006—the day after Mel’s infamous drunk driving bust in Malibu, where he had the audacity of spouting anti-Semitic remarks fit for a medieval serf to turn pale. Robyn’s filing for divorce ensued. Chance? Gibson himself confesses not. Life has a way of giving us our plot twists with the subtlety of a wrecking ball, doesn’t she?

The divorce lawsuit lingered on for one of the tax attorneys’ versions of Shakespearean tragedies. In 2011, the bill had exceeded more than $400 million—a handful of small countries’ worth. Not a single prenup, not California state’s community property statutes, and the marriage with the height of his earnings years. That’s the deal when contracts in law are similar to scripts in movies: voluntary reading material that becomes obviously terribly costly.

Language of instruction is English.

Russian Interlude: Poetry, Passion, and Restraining Orders (2008-2011)

Come on stage left Russian pianist and lyricist Oksana Grigorieva with melodrama the equal of a heroine in a Dostoyevsky novel. In her account, Gibson courted her with verse—”edgy, modern iambic pentameter.” Because there’s nothing like being wooed in high-brow verse by the fellow whose last romantic overture had more likely been grunting approval over the dinner table.

Just picture this affair: A Hollywood actor, shaken by a contentious divorce, dating a classical singer with what must have seemed like a befuddled Shakespeare struggling with the meaning of life. Did she swoon on the line, or was she impressed he knew the definition of iambicpentameter?

Their little one Lucia was born in October 2009, but by April 2010, the love had escalated into a litigators’ soap opera to bring John Grisham tears of jealousy. Restraining orders flew back and forth like letters between belligerent states. Audio tapes emerged with Gibson dishing out cuss-word-belching diatribes to have the sailor calling for subtitles.

In a single stroke, the talent reps dumped clients, the movie studios terminated contracts, and Gibson stood in a courtroom making a plea of no contest to the misdemeanor offense of battery. His rationale? A “terribly awful moment in time” at “the height of a breakdown.” We’ve all had relationship breakdows, but who among us requires TMZ headlines and payout settlements to escape romantic catastrophes?

Settlement in 2011: $750,000, shared custody, and a house in Sherman Oaks until the age of 18 for Lucia. Not the rom-com the world had in mind but maybe the ending everyone so hoped for.

The Horse Riding Author: Third Time’s the Charm? (2014-Present)

By 2014, Gibson had fallen in love once more with Rosalind Ross, the former champion equestrian vaulter turned screenwriter. Finally, someone who could coexist in body and mind with a wild ride both personally and professionally. Ross had the particular skills one had to possess in order to date Mel Gibson: athleticism, creativity, and probably the emotional maturity of the person who managed riding thousand-pound creatures.

Their difference in ages brought eyebrows up—Gibson, 60, and Ross, 26—but Hollywood has long played by different mathematical principles when dealing with love stories. While other mortals would disapprove of such matches, Hollywood winks and pours bubbly champagne. Ross welcomed Lars Gerard in January of 2017, Gibson’s ninth child. At this point, one wonders if Mel took franchising his children’s play center complex into consideration. Nine kids in almost four decades places Gibson on the brink of having spent more time in his life changing diapers than some individuals have spent on the planet earth. He should win the parental lifetime achievement award.

Philosophical Implications: What Love Has to Offer

What deep insights do we glean on Gibson’s love life timeline? That Hollywood romance obeys the laws of physics unknown to mortal men? That one can’t buy happiness but will gladly pay for famously costly despair? That even the Mad Max of the world can’t deal with the cosmic tumult of modern romance?

Consider this: Gibson’s love affair has created more onscreen plot turns than the rest of his body of work combined. Each relationship came with different lessons—security and faithfulness with Robyn, passion and destructiveness with Oksana, and perhaps, wisdom and balance with Ross. His love affair is a master class in human psychology with case studies in commitment, infidelity, redemption, and the ultimate hope this time things will be different. Gibson’s narrative teaches us something that is universal about ourselves: our ability to re-invent ourselves, our hunger for love and intimacy, and our survival of epic personal failures. He’s instructed us that celebrity serves to reveal both our virtues and our vices and transforms personal ailments into public exhibitions that somehow echo our shared fascination with love’s epic catastrophes. This much is certain: Gibson’s love story continues to unfold on the pages of one chapter after another. As with the movies he produces, this one has no assured, feel-good ending—only the gritty, grimy, humankind-hilariously complicated journey of finding love with the whole world in the viewing audience.